Intonation on the sitar (& surbahar) is a very complex aspect for players to master due to its unique structure and intricate tuning system. Unlike Western stringed instruments with standardized frets, the sitar’s pardas (frets) are movable, allowing players to adjust the intervals between notes to suit different ragas or tonal structures. This flexibility, while beneficial for musical expression, also creates a challenge in maintaining acceptable intonation. Even slight misplacement of a parda can alter the pitch and compromise the player’s comfort and impact the performance.

Achieving nearly perfect intonation on a sitar & surbahar requires a lot of attention to detail, advanced tuning skills and adjustments. In consultation with Jan van Beek, I designed intonation blocks for his sitar & surbahar. They are made of Elforyn™ and fully tuned to his instruments.

Elforyn™ is a modern synthetic ivory substitute that is very hard-wearing and at the same time easy to work with. Moreover, it has a very natural appearance.

Besides greatly improved intonation, these special blocks have an additional advantage. The distance from the first parda to the meru (comb or nut) increases, making the string longer there. In this way, it becomes possible to play more comfortable and thus more accurate meend on the highest pardas, and especially on the first.

Another case of intonation can be read here.

Tag Archives: tuning

New Narka series

I made a new set of narkas, this time from the wood of an old broomstick (aspen wood). They are done in different colours and a new SiTAR FAcToRY logo is burnt on them. My dear neighbour girl Felien Swillen is very handy with a small wood burner. She burnt the new logo into the wood with razor-sharp precision. The result is impressive.

The mouth of the narka is inlaid with recycled African buffalo leather. This way, the kuntis are not damaged. The outside is finished with shellac polish.

Staghorn Narka

I made a narka out of Belgian stag horn. This is a tuning aid to comfortably and finely tune the taravs, the sympathetic strings on a sitar.

I made a narka out of Belgian stag horn. This is a tuning aid to comfortably and finely tune the taravs, the sympathetic strings on a sitar.

A deer antler hung on the wall. You can find them at old flea markets, or nailed to the wall at hunters’ homes: deer horn antlers as hunting trophies. You can’t do much with them, but for a sitar player you can make a beautiful and useful tool with them.

First choose in a nice and fitting piece, and cut the end generously. Then I make a tapered slot corresponding to the width of the taravs to be operated. A hole is then drilled into it to fit the ornamental tip of the tuning knob, and then I also make the tapered slot suitably concave so that it fits nicely over the tuning knob.

Kunti Hole Bushing

A sitar tuning peg or “kunti” works on the basis of friction. The peg is conically ground and is clamped into a conical hole. After some time, the surfaces will wear out and the peg will go deeper and deeper into the hole. Eventually it comes out deeper and deeper on the other side.

Usually the sitar pegs are made of a hard wood (ebony or rosewood or sheesham) and thus the hole in the neck, which is made of a softer wood (tun or teak), will wear out.

Time to mount new pegs that are a bit thicker. But actually there is nothing wrong with the original tuning pegs. A solution is to provide the holes with a new layer: the kunti bushing.

For this you can use sandpaper of a good quality. The back side, which is made of strong paper, can serve as a layer of wood while the rough sanding side provides an excellent adhesion inside the hole.

It is a matter of cutting out a well-fitting piece of sandpaper and gluing it properly into the hole. Make sure that the sandpaper fits perfectly and does not overlap. Also make sure that no glue gets between the kunti and the bushing. The glue should only be sitting between the rough sandpaper-side and the hole in the neck.

You can use the peg itself to fit the sandpaper in the hole and as a clamp to keep the sandpaper in place while drying.

When everything is dry, you can cut away the excess piece of sandpaper with a sharp chisel.

In this way, the original pegs can continue to be used.

Keep in mind that this bushing will have to be replaced after a while. The paper will wear out faster than the wood of the neck. It is best to look out for professional quality sandpaper. Then you will be at ease for a long time!

See more at this new Repairs-page: Kunti Bushing

Dagar Tanpura

Ud H. Sayeeduddin Dagar, a great dhrupad singer, cousin uncle from the legendary Dagar brothers, frequently visits Belgium for concerts and teachings. Because travelling with big tanpuras is not easy and not without risk, Dagarji has kept a couple of them here resident for this purpose. Recently, a huge, very old and worn tanpura was in the shop. It was made by famous tanpuramakers from Miraj: Abdul Sattar & Hadji Abdul Karim. There was a minor tumba crack to be repaired and a new jawari to be fitted. The ghoraj, specially made for Dagarji, came as a massive and impressive plain staghorn piece, with a big, very roughly curved surface. Firstly I have made this surface smooth and softly rounded with a coarse file. After that I used soft blocks of upgrading sandpaper to polish the curving perfectly to its final shape.

Ud H. Sayeeduddin Dagar, a great dhrupad singer, cousin uncle from the legendary Dagar brothers, frequently visits Belgium for concerts and teachings. Because travelling with big tanpuras is not easy and not without risk, Dagarji has kept a couple of them here resident for this purpose. Recently, a huge, very old and worn tanpura was in the shop. It was made by famous tanpuramakers from Miraj: Abdul Sattar & Hadji Abdul Karim. There was a minor tumba crack to be repaired and a new jawari to be fitted. The ghoraj, specially made for Dagarji, came as a massive and impressive plain staghorn piece, with a big, very roughly curved surface. Firstly I have made this surface smooth and softly rounded with a coarse file. After that I used soft blocks of upgrading sandpaper to polish the curving perfectly to its final shape.

At his request, special thick pins are mounted under the feet to prevent the ghoraj from slipping. Note the amount of holes which were already made in the tabli before. I decided not to make any more other new holes but to use a couple of existing ones.

At his request, special thick pins are mounted under the feet to prevent the ghoraj from slipping. Note the amount of holes which were already made in the tabli before. I decided not to make any more other new holes but to use a couple of existing ones.

Sound sample:

Tanpura in B-flat

The scale (open string length) of this huge instrument is 96,5cms and it is tuned to B-flat.

The Ud H. Sayeeduddin Dagar custom string set is

1: 0,60mm steel string tuned to E#1

2: 0,60mm steel string tuned to A#2

3: 0,60mm steel string tuned to A#2

4: 0,91mm bronze string tuned to A#1

Tuning problem: Cracked wood

On a traditional sitar, tuning is established by pressing a wooden peg (kuti) into a hole. Unfortunately the wood on this Barun Ray sitar is cleaved. There is a long and deep split line between the baj and jora kuti. Both strings were not keeping tune anymore. The pegs got loose too easy. How this has happened is difficult to say. Maybe during a transport something has been hitting the kutis and made the wood split. Or maybe that the wood was already damaged at the moment of selection or during the construction of this sitar. Thus weakened, it may got easily split caused by the high pressure coming from the kutis being squeezed into the hole during tuning activities.

But the repair of this defect is not so difficult. First thing to do is to remove the decoration along the head. Then split the upper head plate from the latter curved neck piece.

Repair the crack with glue and, at the same time I ‘ve added a reinforcement piece of wood on the inside. On this piece the grains are running in a perpendicular direction in relation to the wood of the head plate.

Close the head and fix the deco. Finally drill the hole and clean it.

Finish with some fresh shellac and fit the kutis again. Done…

Sitar in E

In the musicschool of Breda (NL) De Nieuwe Veste resides a very inspiring, young sitarteacher. In order to motivate new pupils he teaches them first to play rather light classical music and easy popular tunes. Therefore they need their student sitar being tuned in E (instead of C#). Notes have to be shifted from C# to E and because of the rather high shift we have been fitting a very light string set.

Extra light string set:

Baj = N°2 = 0,28mm steel

Jora = N°3 = 0,30mm steel

Laraj = N°27 = 0,37mm bronze

Kharaj = N°25 = 0,51mm bronze

Pancham = N°1 = 0,25mm steel

Cikari = N°00 = 0,19mm steel

The sitar now plays very light and easy and results in a sharp but rich and funny, jolly sound.

Sound sample:

Sitar in E

Dead notes

In music, a ghost note, dead note, or false note, is a musical note with a rhythmic value, but no discernible pitch when played. On stringed instruments, this is recognised by the sound of a muted string. Muted to the point where it is more percussive sounding than obvious and clear in pitch. There is a pitch, to be sure, but its musical value is more rhythmic than melodic or harmonic… (source = wikipedia)

Until now I haven’t been confronted with severe dead notes problems yet. I have experienced the phenomenon a couple of times, but not at such a degree that my clients have asked me to intervene.

But it happens that one of my wife’s sitars suffers from this, and recently an extra occasion came with this mail by Toss Levy: “… Dead notes on a sitar have always been a problem. Mostly by careful jawari and work on the taraf bridge and strings, I could get a better resonance. I have found dead-notes to be on most instruments and consider the instruments with a responsive resonance over the entire note range rare but of super quality. For me, and maybe in my ignorance, I have accepted the dead-notes as a sign of a lesser quality instruments… How does one go about solving the dead-note problem ??…” :

From my school-time I always remember an important basic physics law about acoustic resonance (source = wikipedia):

![]()

k = stiffness

m = mass

ωn = radian frequency (radians per second)

From the radian frequency, the natural frequency, fn, can be found by simply dividing ωn by 2π. Without first finding the radian frequency, the natural frequency can be found directly using:

![]()

k = stiffness (Newtons/meter or N/m)

m = mass(kg)

fn = natural frequency in hertz (cycles/second)

This equation tells me that the resonance frequency is proportional to the stiffness and inversely proportional to the mass of an acoustic system. It sounds logical, and gives us a rather simple tool to influence the phenomenon:

Working on the stiffness includes interfering in the instruments basic wooden construction: tabli, tumba, neck, joint etc. …  But this is uttermost time consuming and almost impossible to experiment with, and surely not, on an expensive well-built sitar.

But this is uttermost time consuming and almost impossible to experiment with, and surely not, on an expensive well-built sitar.

But working on the mass can be done very easy: I did some experiments on adding mass to the ghodi (jawari – bridge construction) and the result is very promising. I have prepared and selected a couple of metal parts (lead) ranging from 10g, 20g, 30g,… to 150g and attached these one by one to the ghodi. And as the formula predicts, the resonance frequency is really shifting down. In my case, with 30g added, from komal GA towards main tonic SA where the amplitude of the resonance has been reduced such that it is almost not heard anymore.

Results (sound samples):

Results (sound samples):

1: original jawari (nothing added)

2: jawari + 10 grams added

3: jawari + 20 grams added

4: jawari + 30 grams added

5: jawari + 50 grams added

6: jawari + 100 grams added

7: jawari + 150 grams added

Comments on the results:

1: Dead note is clearly heard on komal GA, also noticeable on GA. (Never mind the missed NI…).

2: Dead note is already reduced in amplitude and slightly shifts towards RE.

3: Dead notes amplitude is even more reduced and shifts over RE.

4: Dead note is now almost disappeared, reaching SA.

5: Dead note is now completely gone, but the overall sound is losing low frequency range because of the damping effect of the weight.

6 & &7: The overall sound loses more and more low frequencies because of an increased damping effect.

Some considerations:

Adding a weight to the jawari can be compared to the act of adjusting a kind of acoustic audiofilter. This implicates that when talking about acoustic waves there are always 3 parameters to keep in mind: fo, the frequency itself; A, the amplitude (how strong is the influence) and Q, the quality factor which is related to Δf, the bandwidth. This means that adjacent frequencies are involved in the proces.

Adding a weight to the jawari can be compared to the act of adjusting a kind of acoustic audiofilter. This implicates that when talking about acoustic waves there are always 3 parameters to keep in mind: fo, the frequency itself; A, the amplitude (how strong is the influence) and Q, the quality factor which is related to Δf, the bandwidth. This means that adjacent frequencies are involved in the proces. ![]() The lower the quality factor, the bigger influence will be noticeable on adjacent notes or srutis too. This one can be determinative for the result.

The lower the quality factor, the bigger influence will be noticeable on adjacent notes or srutis too. This one can be determinative for the result.

Unfortunately it is not a linear but an exponential equation. The result of the operation becomes stronger and stronger OR lesser and lesser at an exponential rate… This means that the practical adjustable range will be limited, and probably difficult to measure. Trouble might be to find a good starting weight. But, patience is a golden virtue…

Swarangini Modification

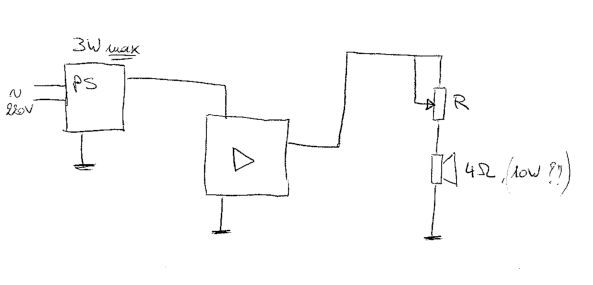

Swarangini Digital is an electronic tanpura machine that delivers high quality original tanpura sounds. It has been introduced to the market in 2008. For more info about this very handy and popular machine visit the Sound Labs website. The machine is excellent for tuning and accompaniment. But, since this is a digital machine, it has a big disadvantage: the main volume is not anymore adjusted continuously but in steps. And, unfortunately, these steps are rather big, especially in the lower volume regions. Also the lowest sound ever is still much too loud in many occasions such as practice at home.

Swarangini Digital is an electronic tanpura machine that delivers high quality original tanpura sounds. It has been introduced to the market in 2008. For more info about this very handy and popular machine visit the Sound Labs website. The machine is excellent for tuning and accompaniment. But, since this is a digital machine, it has a big disadvantage: the main volume is not anymore adjusted continuously but in steps. And, unfortunately, these steps are rather big, especially in the lower volume regions. Also the lowest sound ever is still much too loud in many occasions such as practice at home.

The most simple and very adequate solution is to create yourself an analog volume fine tuning knob by putting a potmeter in series with the loudspeaker. The only consideration which has to be taken into account is that this part of the circuit works under a slightly higher current level since it is the main amplifiers output. So, best is to choose a wire-wounded (high power) potmeter. A value of 50 Ohms, 4 Watts works great.

Open the box by removing the 4 screws and cutting the warranty seal sticker. Drill a 10mm hole through the side and remove the excess plastic on the inside to make room for the potmeter. Fix the potmeter and loosen the black wire which is leading to one of the solder lugs of the speaker. Solder this wire to the middle lug of the potmeter. Take another piece of insulated copperwire and solder it between the adjacent potmeter lug and the speaker lug on which the black wire was attached before. Close the box and mount a nice knob. Thats all for your custom volume finetuning knob…

Travel Sitar Mods (2)

This modification I made to Mark B’s Travel sitar because he was unable to play the jora tar comfortably. The steel wire jora tar, although open correctly tuned, sounded too high while playing a note on the pardas.

I added a fibre intonation block to the jora tar, just as I did with my own made SAS and SBS sitars. Now he can play the jora tar up to the middle note Sa without any problem and accurately without meend.