Intonation on the sitar (& surbahar) is a very complex aspect for players to master due to its unique structure and intricate tuning system. Unlike Western stringed instruments with standardized frets, the sitar’s pardas (frets) are movable, allowing players to adjust the intervals between notes to suit different ragas or tonal structures. This flexibility, while beneficial for musical expression, also creates a challenge in maintaining acceptable intonation. Even slight misplacement of a parda can alter the pitch and compromise the player’s comfort and impact the performance.

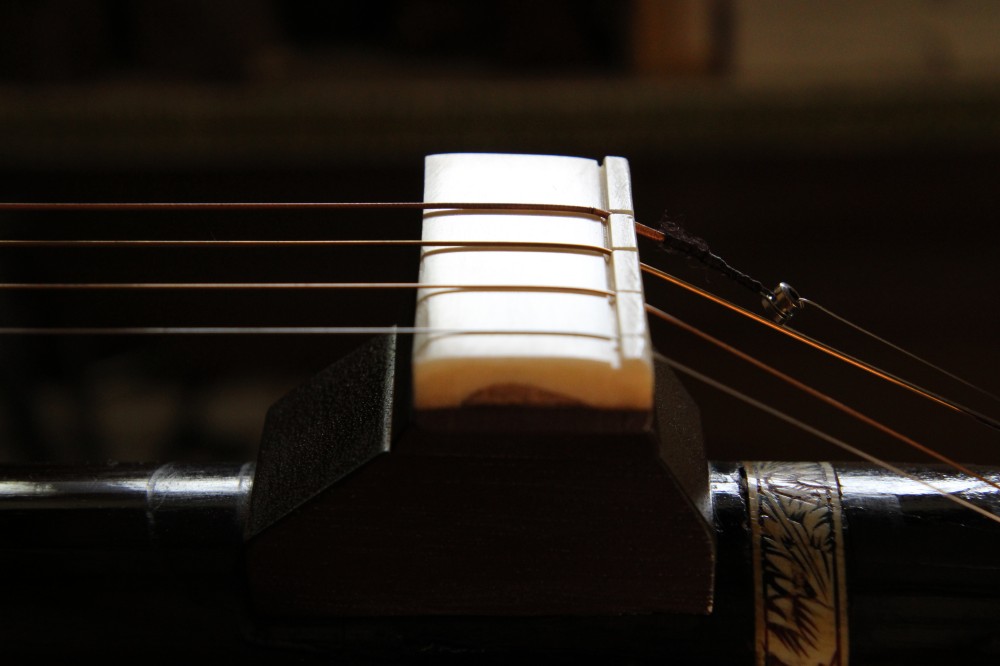

Achieving nearly perfect intonation on a sitar & surbahar requires a lot of attention to detail, advanced tuning skills and adjustments. In consultation with Jan van Beek, I designed intonation blocks for his sitar & surbahar. They are made of Elforyn™ and fully tuned to his instruments.

Elforyn™ is a modern synthetic ivory substitute that is very hard-wearing and at the same time easy to work with. Moreover, it has a very natural appearance.

Besides greatly improved intonation, these special blocks have an additional advantage. The distance from the first parda to the meru (comb or nut) increases, making the string longer there. In this way, it becomes possible to play more comfortable and thus more accurate meend on the highest pardas, and especially on the first.

Another case of intonation can be read here.

Tag Archives: ghoraj

Juma Mankas

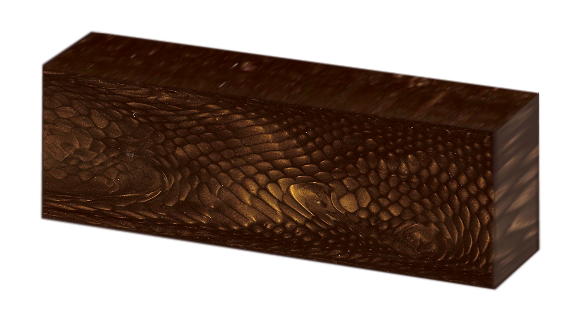

I’ve made a set of mankas and one tarav ghoraj for Zach Ferrara.

They are made out of golden dragon snake Juma® blocs. Juma® – the name stands for independently developed and very modern processing material made from a mixture of various mineral base materials, bound in a resin component. Just like Elforyn® is Juma® excellently suited for the production of components and artistic objects such as knife handles, jewelry, eyeglass frames, or music instrument parts. “Produce your own custom items and delight in genuine one-of-a-kind pieces that no one else will be able to imitate.” the website says.

The material is indeed easy to work with and the result feels very natural and pleasant. The optical effect is stunning and has a nice impression of depth. It is definitely very suitable for decorations, mankas and possibly a tarav ghoraj. But I think it has too little resistance to wear to be suitable for a main ghoraj. Elforyn®, on the other hand, does well. Follow this link for Elforyn® examples.

In any case, it looks impressive on Zach’s beautiful sitar. The manka of the main string is made a little bigger than that of the other strings.

Rudra Veena repair

This anonymous rudra veena was found by my friend Guillaume CZLT in Bombay Pekin Bruxelles, a shop for second-hand furniture in Brussels. It was quite badly damaged. One of the tumbas was badly broken, the main bridge had been torn off and lost, and all the frets had been worn away. The fretboard looked more like a pattata field. All the frets were loose and crooked on the neck. A cikari pin was broken… and one day there must have been strings on the instrument…?

This anonymous rudra veena was found by my friend Guillaume CZLT in Bombay Pekin Bruxelles, a shop for second-hand furniture in Brussels. It was quite badly damaged. One of the tumbas was badly broken, the main bridge had been torn off and lost, and all the frets had been worn away. The fretboard looked more like a pattata field. All the frets were loose and crooked on the neck. A cikari pin was broken… and one day there must have been strings on the instrument…? The work started with repairing the broken tumba. I counted 27 pieces (or small pieces) and 3 appeared to be missing. The puzzle was put back together in 5 stages. Fortunately, everything still fitted well and the transitions are usually smooth. A few coats of varnish over the whole finished this part. Colour matching was not done at this stage.

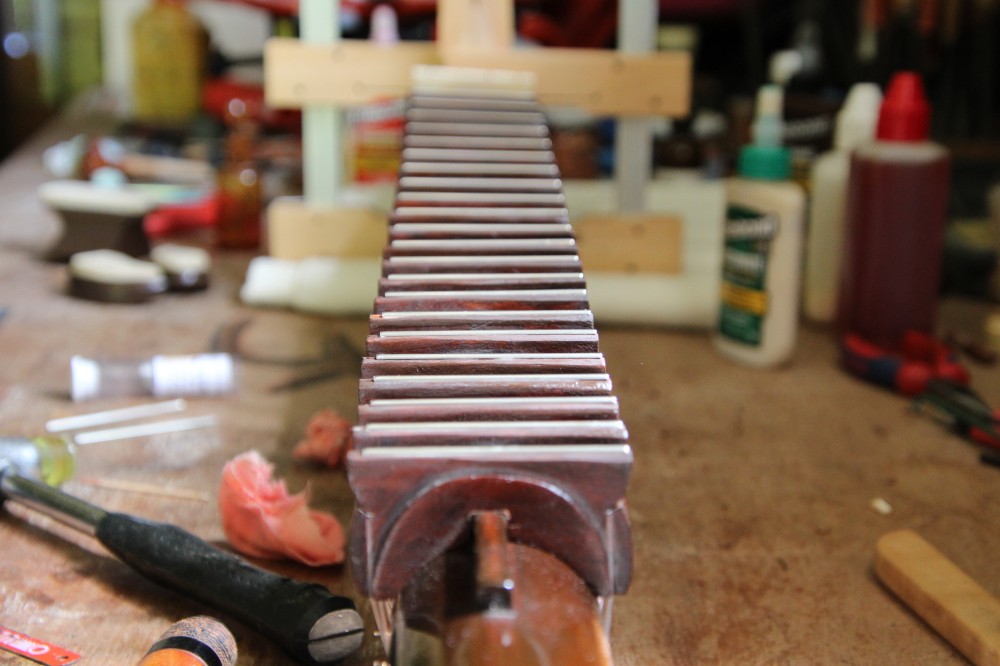

The work started with repairing the broken tumba. I counted 27 pieces (or small pieces) and 3 appeared to be missing. The puzzle was put back together in 5 stages. Fortunately, everything still fitted well and the transitions are usually smooth. A few coats of varnish over the whole finished this part. Colour matching was not done at this stage. After that, the frets were taken in hand. The old aluminium strips were easily lifted out of the holder. I ordered a set of 24 new pre-cut pieces of fret wire Wagner 9671 Nickel Silver Frets, Large/Jumbo, with dimensions (W x L x H): 70 x 2,75 x 3,2 mm. But first the fret holders all had to be made equal and properly attached to the central guiding shaft. And this one was crooked and irregular too. With a little trick I could get all the frets nicely in one row and fix them firmly in place. After that, I made the top even and flat and finally installed the new frets. That looks good!

After that, the frets were taken in hand. The old aluminium strips were easily lifted out of the holder. I ordered a set of 24 new pre-cut pieces of fret wire Wagner 9671 Nickel Silver Frets, Large/Jumbo, with dimensions (W x L x H): 70 x 2,75 x 3,2 mm. But first the fret holders all had to be made equal and properly attached to the central guiding shaft. And this one was crooked and irregular too. With a little trick I could get all the frets nicely in one row and fix them firmly in place. After that, I made the top even and flat and finally installed the new frets. That looks good! The last part is the new ghodi. A round base that is glued to the neck gets a nice straight surface. On top of that comes a removable ghodi that is firmly held in place by two metal pins. Quite a construction, but in the end it fits nicely on the whole. Because the upper part is removable, you can easily do jawari at any time. Now all that’s left is to put new strings on it…

The last part is the new ghodi. A round base that is glued to the neck gets a nice straight surface. On top of that comes a removable ghodi that is firmly held in place by two metal pins. Quite a construction, but in the end it fits nicely on the whole. Because the upper part is removable, you can easily do jawari at any time. Now all that’s left is to put new strings on it… I think Guillaume will be pleased… 😉

I think Guillaume will be pleased… 😉

Technical info on strings & tuning according to Asad Ali Khan style:

The scale measures 945cm & the instrument is tuned to G#

Cikari’s: steel 0,30mm (N°3) tuned to G#3 (SA) & G#4 (SA)

Baj tar: steel 0,40mm (N°6) tuned to C#2 (MA)

SA tar: bronze 0,56mm (N°24) tuned to G#2 (SA)

PA tar: bronze 0,72mm (N°22) tuned to D#2 (PA)

Kharaj: flatwound bronze 0,92mm (N°20) tuned to G#1 (SA)

Laraj: bronze 0,56mm (N°24) tuned to G#2 (SA)

For more info about rudra veena you can visit www.rudravina.com and www.rudraveena.org

For more info about rudra veena you can visit www.rudravina.com and www.rudraveena.org

Hiren Roy 70’s refurbish

More Dieter Zarnitz ghoraj

A new set of ghorajs made by Dieter Zarnitz. The wood comes from leftover pieces of a construction.

“Cumaru” is a very fine, hard and durable construction-wood. “Angelim Amargoso” is very heavy and rougher than Cumaru. Both grow in South America. The colour you see is the natural one. The setting (“jawari“) can be done at the Sitar Factory (Belgium).

Dagar Tanpura

Ud H. Sayeeduddin Dagar, a great dhrupad singer, cousin uncle from the legendary Dagar brothers, frequently visits Belgium for concerts and teachings. Because travelling with big tanpuras is not easy and not without risk, Dagarji has kept a couple of them here resident for this purpose. Recently, a huge, very old and worn tanpura was in the shop. It was made by famous tanpuramakers from Miraj: Abdul Sattar & Hadji Abdul Karim. There was a minor tumba crack to be repaired and a new jawari to be fitted. The ghoraj, specially made for Dagarji, came as a massive and impressive plain staghorn piece, with a big, very roughly curved surface. Firstly I have made this surface smooth and softly rounded with a coarse file. After that I used soft blocks of upgrading sandpaper to polish the curving perfectly to its final shape.

Ud H. Sayeeduddin Dagar, a great dhrupad singer, cousin uncle from the legendary Dagar brothers, frequently visits Belgium for concerts and teachings. Because travelling with big tanpuras is not easy and not without risk, Dagarji has kept a couple of them here resident for this purpose. Recently, a huge, very old and worn tanpura was in the shop. It was made by famous tanpuramakers from Miraj: Abdul Sattar & Hadji Abdul Karim. There was a minor tumba crack to be repaired and a new jawari to be fitted. The ghoraj, specially made for Dagarji, came as a massive and impressive plain staghorn piece, with a big, very roughly curved surface. Firstly I have made this surface smooth and softly rounded with a coarse file. After that I used soft blocks of upgrading sandpaper to polish the curving perfectly to its final shape.

At his request, special thick pins are mounted under the feet to prevent the ghoraj from slipping. Note the amount of holes which were already made in the tabli before. I decided not to make any more other new holes but to use a couple of existing ones.

At his request, special thick pins are mounted under the feet to prevent the ghoraj from slipping. Note the amount of holes which were already made in the tabli before. I decided not to make any more other new holes but to use a couple of existing ones.

Sound sample:

Tanpura in B-flat

The scale (open string length) of this huge instrument is 96,5cms and it is tuned to B-flat.

The Ud H. Sayeeduddin Dagar custom string set is

1: 0,60mm steel string tuned to E#1

2: 0,60mm steel string tuned to A#2

3: 0,60mm steel string tuned to A#2

4: 0,91mm bronze string tuned to A#1

Dieter Zarnitz ghoraj

These ghorajs are made by Dieter Zarnitz. He has copied the Barun Roy and Hari Chand style exactly. The feet are from maple or rosewood, the tops out of snakewood, rosewood or Elforyn™. The setting (“jawari“) can be done at the Sitar Factory (Belgium).

SAS-01 “Black buffalo” edition

Since the good old stagghorn becomes more and more rare, we are in constant seek for a valid alternative. One of the contenders is the black buffalo horn. Buffalo horn plates are used as material for engraving, for pocket knives, tang blades and japanese cooking knives. The plates are partially covered by bright, natural growth patterns and after polishing it becomes shiny and very durable. The sound is something between stagghorn and ebony. Dense, clear and very warm. Very promising !!

Black buffalo horn plate, as sold at Nordisches Handwerk website.

I’ve made a complete new hardware set out of black buffalo horn for my SAS-01 semi-acoustic sitar: ghoraj (main bridge), langoot (tail mount), mogara (cikari posts) and patri (neck bridge). And it looks good !! Click the pictures for fancy-zoom. 🙂

Dead notes

In music, a ghost note, dead note, or false note, is a musical note with a rhythmic value, but no discernible pitch when played. On stringed instruments, this is recognised by the sound of a muted string. Muted to the point where it is more percussive sounding than obvious and clear in pitch. There is a pitch, to be sure, but its musical value is more rhythmic than melodic or harmonic… (source = wikipedia)

Until now I haven’t been confronted with severe dead notes problems yet. I have experienced the phenomenon a couple of times, but not at such a degree that my clients have asked me to intervene.

But it happens that one of my wife’s sitars suffers from this, and recently an extra occasion came with this mail by Toss Levy: “… Dead notes on a sitar have always been a problem. Mostly by careful jawari and work on the taraf bridge and strings, I could get a better resonance. I have found dead-notes to be on most instruments and consider the instruments with a responsive resonance over the entire note range rare but of super quality. For me, and maybe in my ignorance, I have accepted the dead-notes as a sign of a lesser quality instruments… How does one go about solving the dead-note problem ??…” :

From my school-time I always remember an important basic physics law about acoustic resonance (source = wikipedia):

![]()

k = stiffness

m = mass

ωn = radian frequency (radians per second)

From the radian frequency, the natural frequency, fn, can be found by simply dividing ωn by 2π. Without first finding the radian frequency, the natural frequency can be found directly using:

![]()

k = stiffness (Newtons/meter or N/m)

m = mass(kg)

fn = natural frequency in hertz (cycles/second)

This equation tells me that the resonance frequency is proportional to the stiffness and inversely proportional to the mass of an acoustic system. It sounds logical, and gives us a rather simple tool to influence the phenomenon:

Working on the stiffness includes interfering in the instruments basic wooden construction: tabli, tumba, neck, joint etc. …  But this is uttermost time consuming and almost impossible to experiment with, and surely not, on an expensive well-built sitar.

But this is uttermost time consuming and almost impossible to experiment with, and surely not, on an expensive well-built sitar.

But working on the mass can be done very easy: I did some experiments on adding mass to the ghodi (jawari – bridge construction) and the result is very promising. I have prepared and selected a couple of metal parts (lead) ranging from 10g, 20g, 30g,… to 150g and attached these one by one to the ghodi. And as the formula predicts, the resonance frequency is really shifting down. In my case, with 30g added, from komal GA towards main tonic SA where the amplitude of the resonance has been reduced such that it is almost not heard anymore.

Results (sound samples):

Results (sound samples):

1: original jawari (nothing added)

2: jawari + 10 grams added

3: jawari + 20 grams added

4: jawari + 30 grams added

5: jawari + 50 grams added

6: jawari + 100 grams added

7: jawari + 150 grams added

Comments on the results:

1: Dead note is clearly heard on komal GA, also noticeable on GA. (Never mind the missed NI…).

2: Dead note is already reduced in amplitude and slightly shifts towards RE.

3: Dead notes amplitude is even more reduced and shifts over RE.

4: Dead note is now almost disappeared, reaching SA.

5: Dead note is now completely gone, but the overall sound is losing low frequency range because of the damping effect of the weight.

6 & &7: The overall sound loses more and more low frequencies because of an increased damping effect.

Some considerations:

Adding a weight to the jawari can be compared to the act of adjusting a kind of acoustic audiofilter. This implicates that when talking about acoustic waves there are always 3 parameters to keep in mind: fo, the frequency itself; A, the amplitude (how strong is the influence) and Q, the quality factor which is related to Δf, the bandwidth. This means that adjacent frequencies are involved in the proces.

Adding a weight to the jawari can be compared to the act of adjusting a kind of acoustic audiofilter. This implicates that when talking about acoustic waves there are always 3 parameters to keep in mind: fo, the frequency itself; A, the amplitude (how strong is the influence) and Q, the quality factor which is related to Δf, the bandwidth. This means that adjacent frequencies are involved in the proces. ![]() The lower the quality factor, the bigger influence will be noticeable on adjacent notes or srutis too. This one can be determinative for the result.

The lower the quality factor, the bigger influence will be noticeable on adjacent notes or srutis too. This one can be determinative for the result.

Unfortunately it is not a linear but an exponential equation. The result of the operation becomes stronger and stronger OR lesser and lesser at an exponential rate… This means that the practical adjustable range will be limited, and probably difficult to measure. Trouble might be to find a good starting weight. But, patience is a golden virtue…

Jawari

Common knowledge

The most radical maintenance work on a sitar is undoubtedly, and most commonly named, “(doing) jawari”. The correct meaning of the word “jawari” (or “jiwari”) is “saddle which gives life to the sound”. It comes from the hindi combination of “jiv” (= life) & “sawari” (= saddle). The actual bridge, as we casually also adress to as “jawari” is in fact called ghoraj or ghodi. This is a construction of wooden legs, glued to a piece of hard material in a rectangular shape and a curved surface. How to make a ghoraj can be seen here.

The legs are made of tun, teak or even sheeshum but also mahogany, ahorn, rosewood or almost any other fine quality wooden leftover piece can be used. The harder the wood, the clearer and louder the sound that will come out. The upper part of the ghoraj, the ghodi, is also made of a hard material. Professional quality sitars are usually fitted with a piece of staghorn. The antlers of the barasingha, a type of deer native to India & Nepal, are most wanted for this but they became very rare and are now protected. Nowadays many sitar makers experiment with synthetic materials. The sound which comes from a fine piece of fiber is a bit different, but at least very useful and comparable to staghorn. And they have a big advantage that they resist wear much more better than any other material such as camel bone, ebony, rosewood, ivory, buffalo horn and staghorn.

Jawari’s basic principles

Very important is the curved shape of the bridge and in particular the narrowing between bridge and string. This is the most important factor, determinating the typical sound of a sitar. Since the bridge is wide (2,5 – 3 cm) the contact with the string is spread over a longer distance. This makes that a vibrating string will have several “touching points” which generate extra harmonics. These create a very rich, complex resonating, almost self entertaining, and evolving buzzing sound.

Two main extremes are to be distinguished

1. Open jawari or “khula” (= open sound, for ex. Ravi Shankar style) is created by a long and wide narrowing between strings and bridge. This combination is full of harmonics and sounds very bright, loud and buzzy.

2. Closed jawari or “band” (= closed sound, for ex. Vilayat Khan & Balaram Pathak style) is created by a rather short and small narrowing between strings and bridge, or even no narrowing at all. This sounds more warm and less, or even not buzzy at all. A great advantage is the high gain in sustain.

These two main types are scarcely found under their extreme form. (Only a tanpura has an extremely open bridge). In reality the sound of the bridge is mostly in between these two types, guided by personal preference and gharana style.

The degree of widening can easily be detected. Put your fingernail on the string and then gently slide with your fingernail perpendicular to the string over the bridge while the string is vibrating. At the point where the bridge becomes open suddenly intense vibrations will be observed.

Workflow

Use long and flat, coarse to second cut files. Depending on the amount of material which should be removed to obtain a desired curve. Or, in case of regular maintenance jawari work the choice of your file may be determined by the amount of wear. Make sure your files are always clean and intact. Fine cut files and sandpaper are used for the finishing touch. A fine clue which Hariji taught me is to use the backside of sandpaper to give a final polishing stroke.

For a good result it is important that you can keep the ghodi surface solid and stable against the file. A very helpfull tool might be a good workbench vice to firmly clamp the ghodi. Or even better, use a traditional Indian floor bench vice. Take a look here if you want to make one yourself.

Doing jawari is a question of practice. No written rules exists on how, where and when to start filing or sanding. Just take your time to create a slow but steady, exponentially inclined curve. At regular times, create a finishing stroke with fine sandpaper and try out on your instrument. Remove it again and work further, step by step. It’s also a good idea not to experiment with your one and only fine staghorn jawari but look out for a piece of cheap camel bone, leftover ebony or fiber and make your own ghoraj from scratch. It might take some time, but once you succeed to create a good sound with a self-made jawari…

Finetuning

When your sound starts to come, you can feel the desire that one or more strings should sound different. For example, you want cikari strings to sound more open than playing strings, or laraj kharaj only to become more closed. From that moment onwards you should work locally by means of a scraper. This is a cutting tool which is used in a perpendicular position towards the surface. Make sure your cutter is not too wide but very sharp and clean. Relax the string and pull it aside. Remove some material by scraping it off. Make the narrowing wider if you want a more open sound, or remove some material from next to the point where the narrowing begins to make the string go deeper and as such making the narrowing smaller to obtain a more closed sound.

Before you start

Note that a jawari is never glued to the tabli. It should always be possible to remove it without force. In case of problem, one can mount one or two very small bone pins to prevent the jawari from sliding away while playing meend. Sometimes a drop of shellack is applied to the feet in order to fix the jawari. But, before you remove a jawari, make sure to be able to put it again in the same position. If needed, mark the feet’s position by making a small incision on the tabli with a sharp knife or chisel.

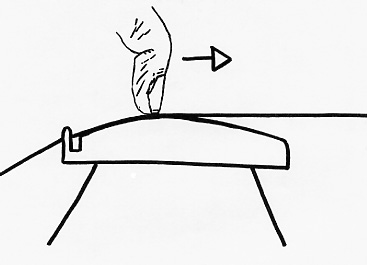

If you want to change the sound more drastically from open to closed sound or reverse, it is better to work on the jawari’s full inclination first. This is done by removing a very small amount of wood from under the jawari’s feet. Removing wood from the frontside onwards, will make the jawari turn over to a wider narrowing with the strings and thus make it sound more open. Removing wood at the backside will make it turn over to a smaller narrowing and make the sound more closed. For this you can use a coarse or second cut file, or cut the wood away with a sharp chisel. Make sure that the feet’s original curve is maintained so that the jawari is in perfect contact surface with the tabli.

A note about dimensions

The dimensions of a sitar’s ghodi can range from 6.5cm x 2.6cm to 7.5cm x 3cm. Smaller bridges are often installed on the older sitars and on Vilayat Khan style sitars (only 6 strings – more closed sound). Ravi Shankar, Nikhil Banerjee etc are more likely to use slightly wider and larger ghodis because they offer more tonal possibilities (open – half-open sound) and because there are one or two more strings on the ghodi.

There is no such thing as the perfect height of a ghodi. It can vary from 2cm (especially old sitars) up to 3.4cm. The final height of the ghodi on your sitar is mainly determined by the action of the strings. This is the distance between the playing string and the fret at the position of the highest note (this is the fret closest to the ghodi – or sometimes the 17th fret, high SA). This distance is best between 8 to 11mm. The height of the ghodi is thus adjusted until you reach an action of approx. 8 to 11mm.

Ready for more ?

How to make a ghodi

Dead notes

Jora tar tuning problem

The Indian floor bench vice

Black buffalo horn