These ghorajs are made by Dieter Zarnitz. He has copied the Barun Roy and Hari Chand style exactly. The feet are from maple or rosewood, the tops out of snakewood, rosewood or Elforyn™. The setting (“jawari“) can be done at the Sitar Factory (Belgium).

SAS-01 “Black buffalo” edition

Since the good old stagghorn becomes more and more rare, we are in constant seek for a valid alternative. One of the contenders is the black buffalo horn. Buffalo horn plates are used as material for engraving, for pocket knives, tang blades and japanese cooking knives. The plates are partially covered by bright, natural growth patterns and after polishing it becomes shiny and very durable. The sound is something between stagghorn and ebony. Dense, clear and very warm. Very promising !!

Black buffalo horn plate, as sold at Nordisches Handwerk website.

I’ve made a complete new hardware set out of black buffalo horn for my SAS-01 semi-acoustic sitar: ghoraj (main bridge), langoot (tail mount), mogara (cikari posts) and patri (neck bridge). And it looks good !! Click the pictures for fancy-zoom. 🙂

Dead notes

In music, a ghost note, dead note, or false note, is a musical note with a rhythmic value, but no discernible pitch when played. On stringed instruments, this is recognised by the sound of a muted string. Muted to the point where it is more percussive sounding than obvious and clear in pitch. There is a pitch, to be sure, but its musical value is more rhythmic than melodic or harmonic… (source = wikipedia)

Until now I haven’t been confronted with severe dead notes problems yet. I have experienced the phenomenon a couple of times, but not at such a degree that my clients have asked me to intervene.

But it happens that one of my wife’s sitars suffers from this, and recently an extra occasion came with this mail by Toss Levy: “… Dead notes on a sitar have always been a problem. Mostly by careful jawari and work on the taraf bridge and strings, I could get a better resonance. I have found dead-notes to be on most instruments and consider the instruments with a responsive resonance over the entire note range rare but of super quality. For me, and maybe in my ignorance, I have accepted the dead-notes as a sign of a lesser quality instruments… How does one go about solving the dead-note problem ??…” :

From my school-time I always remember an important basic physics law about acoustic resonance (source = wikipedia):

![]()

k = stiffness

m = mass

ωn = radian frequency (radians per second)

From the radian frequency, the natural frequency, fn, can be found by simply dividing ωn by 2π. Without first finding the radian frequency, the natural frequency can be found directly using:

![]()

k = stiffness (Newtons/meter or N/m)

m = mass(kg)

fn = natural frequency in hertz (cycles/second)

This equation tells me that the resonance frequency is proportional to the stiffness and inversely proportional to the mass of an acoustic system. It sounds logical, and gives us a rather simple tool to influence the phenomenon:

Working on the stiffness includes interfering in the instruments basic wooden construction: tabli, tumba, neck, joint etc. …  But this is uttermost time consuming and almost impossible to experiment with, and surely not, on an expensive well-built sitar.

But this is uttermost time consuming and almost impossible to experiment with, and surely not, on an expensive well-built sitar.

But working on the mass can be done very easy: I did some experiments on adding mass to the ghodi (jawari – bridge construction) and the result is very promising. I have prepared and selected a couple of metal parts (lead) ranging from 10g, 20g, 30g,… to 150g and attached these one by one to the ghodi. And as the formula predicts, the resonance frequency is really shifting down. In my case, with 30g added, from komal GA towards main tonic SA where the amplitude of the resonance has been reduced such that it is almost not heard anymore.

Results (sound samples):

Results (sound samples):

1: original jawari (nothing added)

2: jawari + 10 grams added

3: jawari + 20 grams added

4: jawari + 30 grams added

5: jawari + 50 grams added

6: jawari + 100 grams added

7: jawari + 150 grams added

Comments on the results:

1: Dead note is clearly heard on komal GA, also noticeable on GA. (Never mind the missed NI…).

2: Dead note is already reduced in amplitude and slightly shifts towards RE.

3: Dead notes amplitude is even more reduced and shifts over RE.

4: Dead note is now almost disappeared, reaching SA.

5: Dead note is now completely gone, but the overall sound is losing low frequency range because of the damping effect of the weight.

6 & &7: The overall sound loses more and more low frequencies because of an increased damping effect.

Some considerations:

Adding a weight to the jawari can be compared to the act of adjusting a kind of acoustic audiofilter. This implicates that when talking about acoustic waves there are always 3 parameters to keep in mind: fo, the frequency itself; A, the amplitude (how strong is the influence) and Q, the quality factor which is related to Δf, the bandwidth. This means that adjacent frequencies are involved in the proces.

Adding a weight to the jawari can be compared to the act of adjusting a kind of acoustic audiofilter. This implicates that when talking about acoustic waves there are always 3 parameters to keep in mind: fo, the frequency itself; A, the amplitude (how strong is the influence) and Q, the quality factor which is related to Δf, the bandwidth. This means that adjacent frequencies are involved in the proces. ![]() The lower the quality factor, the bigger influence will be noticeable on adjacent notes or srutis too. This one can be determinative for the result.

The lower the quality factor, the bigger influence will be noticeable on adjacent notes or srutis too. This one can be determinative for the result.

Unfortunately it is not a linear but an exponential equation. The result of the operation becomes stronger and stronger OR lesser and lesser at an exponential rate… This means that the practical adjustable range will be limited, and probably difficult to measure. Trouble might be to find a good starting weight. But, patience is a golden virtue…

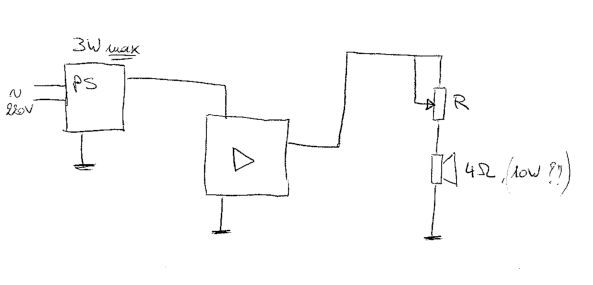

Swarangini Modification

Swarangini Digital is an electronic tanpura machine that delivers high quality original tanpura sounds. It has been introduced to the market in 2008. For more info about this very handy and popular machine visit the Sound Labs website. The machine is excellent for tuning and accompaniment. But, since this is a digital machine, it has a big disadvantage: the main volume is not anymore adjusted continuously but in steps. And, unfortunately, these steps are rather big, especially in the lower volume regions. Also the lowest sound ever is still much too loud in many occasions such as practice at home.

Swarangini Digital is an electronic tanpura machine that delivers high quality original tanpura sounds. It has been introduced to the market in 2008. For more info about this very handy and popular machine visit the Sound Labs website. The machine is excellent for tuning and accompaniment. But, since this is a digital machine, it has a big disadvantage: the main volume is not anymore adjusted continuously but in steps. And, unfortunately, these steps are rather big, especially in the lower volume regions. Also the lowest sound ever is still much too loud in many occasions such as practice at home.

The most simple and very adequate solution is to create yourself an analog volume fine tuning knob by putting a potmeter in series with the loudspeaker. The only consideration which has to be taken into account is that this part of the circuit works under a slightly higher current level since it is the main amplifiers output. So, best is to choose a wire-wounded (high power) potmeter. A value of 50 Ohms, 4 Watts works great.

Open the box by removing the 4 screws and cutting the warranty seal sticker. Drill a 10mm hole through the side and remove the excess plastic on the inside to make room for the potmeter. Fix the potmeter and loosen the black wire which is leading to one of the solder lugs of the speaker. Solder this wire to the middle lug of the potmeter. Take another piece of insulated copperwire and solder it between the adjacent potmeter lug and the speaker lug on which the black wire was attached before. Close the box and mount a nice knob. Thats all for your custom volume finetuning knob…

Right to left hand modification

Modifying a sitar from right-hand play to left-hand play…

It is not easy to find a suitable sitar if you are left-handed and want to engage yourself into the world of sitar playing. There are good left-hand sitars for sale, but they are very rare and if you find one than there is still the price tag. So, why not modifying a regular sitar from right-hand play to left-hand play ?

Is it always possible ? Unfortunately the answer is no. Since the modern times sitars are more and more build a-symmetrically. In order to improve the meend-playability, the neck of a sitar is mounted slightly (… or more… and more) tilted. This is for our purpose the main downside…

Another one is that the kutis are to be changed from “upside” to “downside”. It will work, but on the new “downside” the holes will be too big. So, the kutis, and thus the tuning of the instrument might become some unstable. Practically, in many cases this will not become a very big issue. It is more of a theoretical matter but at some extreme cases…??

Next to the kutis comes the langoot (tail mount). This very important piece has to be shifted over the center to the right. No big deal at first, but before acting make sure that the wooden tailpiece which is mounted on the inside of the tumba is big enough to reach this new position because the peel of the gourd alone will never hold the high forces induced by all the strings on the langoot.

Last but not least the pardas are to be reversed too. Also here some luck is very welcome to prevent a lot of extra work. If the parda lanes are not nicely even and flat, one risks that on a certain moment the strings are starting to touch the adjacent parda. If this happens, then there is a big chance that you’ll have to reshape all of the following pardas… On this sitar, we decided not to reverse the pardas since they are pretty symmetrical from origine. Finally, the string position notches on the jawari are to be changed and the cikari pins symmetrically reversed. New strings are mounted.

The result looks a little strange because the jawari had to be shifted out of the tablis center, but this instrument is pretty good playable. So, very soon now the first lesson can be arranged…

Belgisk – Dansk Veena Guitar

Here is another unique combination: a fusion between a guitar and a veena. The concept has been developed and build by Shintai who was born in Belgium and now lives in Denmark. He frequently plays meditative concerts on this remarkable instrument.

Here is another unique combination: a fusion between a guitar and a veena. The concept has been developed and build by Shintai who was born in Belgium and now lives in Denmark. He frequently plays meditative concerts on this remarkable instrument.

Shintai on his Veena Guitar

Basically the instrument consists of a bass guitar-neck fitted on an acoustic guitar body. It has 7 main strings, 12 taravs & 23 specially shaped pardas. The 5 highest notes, located on the soundboard, are fixed while the remaining 18 are moveable. The instrument’s impressive head accommodates 17 tuning keys. Amongst them are 4 banjo-type tuners pointing to the backside and 2 extra machine heads are mounted on the neck for tuning the cikari strings.

On Shintai’s request I’ve added a regular sitar jawari (Elforyn™) and an extra wide tarav jawari (bone) and also 6 moveable tarav moghara (Elforyn™)

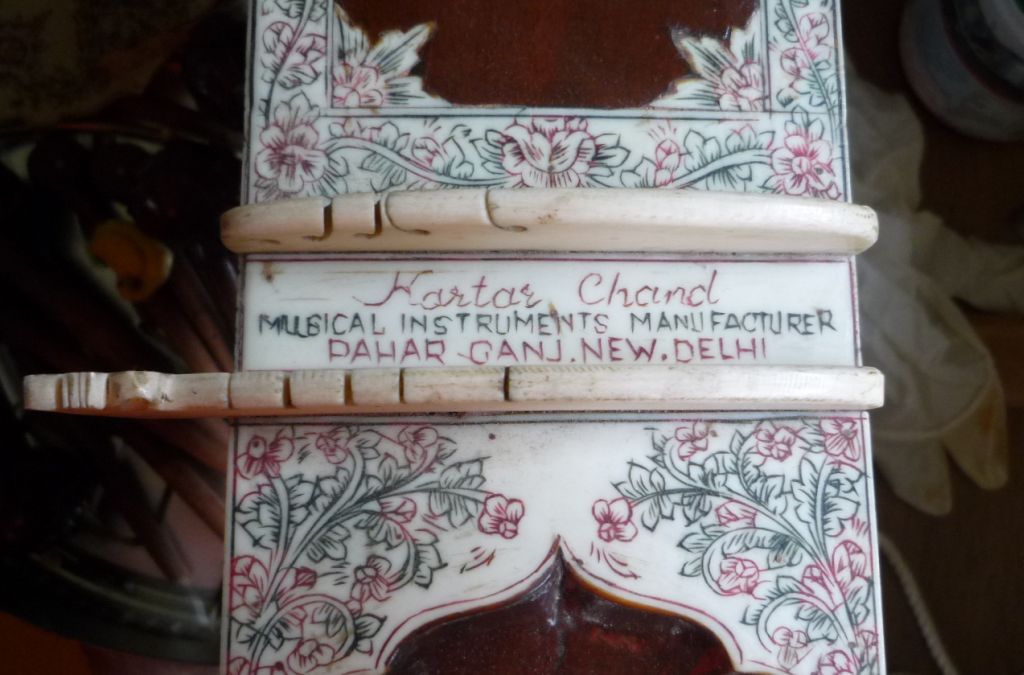

Kartar Chand vintage sitar repair

In 2009, Hari Chand presented me an old sitar which has been originally made by him and his brother, late Kartar Chand, in the 1970’s. The sitar suffered severely from a loose joint due to “an unfortunate fall from a kitchen table”…, dixit the former owner. How peculiar that no other parts of the instrument were broken. Since the owner wasn’t interested in this sitar anymore I was the lucky one to receive it.

In 2009, Hari Chand presented me an old sitar which has been originally made by him and his brother, late Kartar Chand, in the 1970’s. The sitar suffered severely from a loose joint due to “an unfortunate fall from a kitchen table”…, dixit the former owner. How peculiar that no other parts of the instrument were broken. Since the owner wasn’t interested in this sitar anymore I was the lucky one to receive it.

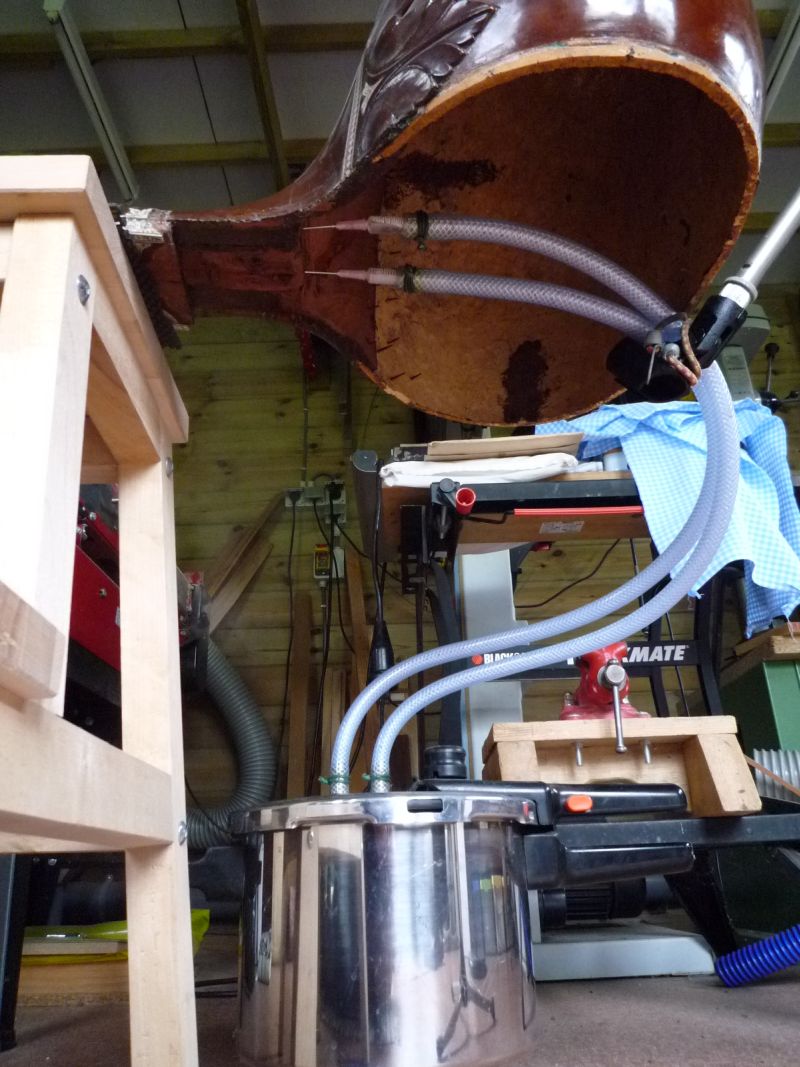

During the second half of this year I finally found the time to repair and fully restore this instrument. Here are some pictures about the more spectacular part of the process. For this occasion I installed my home-made steam injector again. It has been serving me well in the past (click here), although its use is not always completely without risk. The steam can be very tricky and cause severe burns quickly. But everything went well. As for the joint itself: the wood was split at 2 positions due to an earlier joint adjustment. That’s why I decided to insert a completely new piece of wood.

Now this sitar is completely repaired and carefully renovated, ready to start a new life. It is a very light weight instrument, decorated in a very refined and exquisite way. There are 20 pardas, 12 taravs and a high quality staghorn jawari. The sound is superb, bright and clear, with an incredible tarav response. Well-known qualities for all sitars built by these two excellent craftsmen-brothers!

Travel Sitar Mods (3B) … the white sitar

After finalizing the structural rough woodwork on the travel-sitar’s body (see Part 1 = Travel Sitar Mods (3A)) the final acts are: completing the body finish and preparing and installing the sitar’s hardware such as godi (jawari), machine heads, strings, pardas and eventually an electro-magnetic pickup.

I’ve painted the body in white using Bio Pin™ waterbased organic white paint and Colortone™ high gloss waterbased finish. The patri, jawari, cikari machine head mount and cikari posts are all made out of Elforyn™. So it became a real “organic & vegan” sitar,… 100% suitable for vegetarians… 🙂

Installing 7 Schaller™ Mini M6 machine heads and 20 bronze pardas N°6.

Main strings gauges :

1) Baj tar : steel, 0,30mm (N°3)

2) Jora tar : nickel flatwound, 0,46mm (N°26)

3) Laraj tar : nickel flatwound, 0,56mm (N°24)

4) Gandhar tar : steel, 0,30mm (N°3)

5) Pancham tar : steel, 0,30mm (N°3)

6) & 7) Cikari tar : steel, 0,23mm (N°0)

Some details :

Hari Chand Kartar Chand shop closed forever

Today a legendary sitarshop has ceased to exist. Hari Chand, now 77 years old, brother of the founder of this Paharganj based shop, late Kartar Chand Sharma, finaly has definitively closed down the shop. After 50 years, an almost everyday dedicated handicraft in professional sitarmaking came to an end forever. So be it. There is no way back, there are no successors…

You can still virtually visit the shop (click here).

Read the full Kartar Chand Hari Chand history (click here).

More articles about Hari Chand and his work (click here).

Murari Rudra Veena on visit

This very impressive new Rudra Veena came to my workshop for initial setting and jawari. It is now owned by Fabio T., a very enthousiastic ICM adept and young italian filmmaker. This is one of the last rudra veenas made by maestro Murari Mohan Adhikari, the last representative of Kanailal and Brother, worldfamous Calcutta based musical instrument makers. It was originally ordered by late Asad Ali Khan and, although the instrument is already a couple of years old, it has never been played.

This very impressive new Rudra Veena came to my workshop for initial setting and jawari. It is now owned by Fabio T., a very enthousiastic ICM adept and young italian filmmaker. This is one of the last rudra veenas made by maestro Murari Mohan Adhikari, the last representative of Kanailal and Brother, worldfamous Calcutta based musical instrument makers. It was originally ordered by late Asad Ali Khan and, although the instrument is already a couple of years old, it has never been played.

The first thing to do was a proper string setting. I noted that all the strings were mounted very high above the first parda’s position (lowest notes). It was just impossible to play MA tivra from the first fret. The baj tar had to be lowered by approx. 1.5mm on the tar daan to be able to reach the MA tivra correctly. After that, all the pardas were adjusted to their new and correct position on the neck. Adjustments needed for proper intonation to the SA & PA tar & kharaj were only very few.

The first thing to do was a proper string setting. I noted that all the strings were mounted very high above the first parda’s position (lowest notes). It was just impossible to play MA tivra from the first fret. The baj tar had to be lowered by approx. 1.5mm on the tar daan to be able to reach the MA tivra correctly. After that, all the pardas were adjusted to their new and correct position on the neck. Adjustments needed for proper intonation to the SA & PA tar & kharaj were only very few.

The jawari work took almost 8 hours to complete. The original jawari surface was shaped only very roughly. Not a single string had a useful initial sound. Only heavy rattle and clatter came out. But I started to file, scrape and sand, string by string, slowly and steadily and finally realised a smooth and open sound with a stable and long sustain on each note. The only problem I encountered was on the kharaj tar. This 0.92mm plain bronze wire seems to be too stiff to be able to make a proper progressive contact with the jawari’s surface.

The jawari work took almost 8 hours to complete. The original jawari surface was shaped only very roughly. Not a single string had a useful initial sound. Only heavy rattle and clatter came out. But I started to file, scrape and sand, string by string, slowly and steadily and finally realised a smooth and open sound with a stable and long sustain on each note. The only problem I encountered was on the kharaj tar. This 0.92mm plain bronze wire seems to be too stiff to be able to make a proper progressive contact with the jawari’s surface.  This problem sometimes occurs on surbahars and sitars with a somewhat heavy kharaj as well. So I adopted their solution: change the original and ancient plain bronze heavy wire into a modern fine and flexible flatwound bronze on steel string. The result is amazing: A very deep, nicely round and fully evolving open sound with virtually endless sustain. Om Namah Shivaya…

This problem sometimes occurs on surbahars and sitars with a somewhat heavy kharaj as well. So I adopted their solution: change the original and ancient plain bronze heavy wire into a modern fine and flexible flatwound bronze on steel string. The result is amazing: A very deep, nicely round and fully evolving open sound with virtually endless sustain. Om Namah Shivaya…

Technical info on strings & tuning according to Asad Ali Khan style:

Cikari’s: steel 0,30mm (N°3) & 0.25 (N°1) tuned to G#3 (SA) & G#4 (SA)

Baj tar: steel 0,40mm (N°6) tuned to C#2 (MA)

SA tar: bronze 0,56mm (N°24) tuned to G#2 (SA)

PA tar: bronze 0,72mm (N°22) tuned to D#2 (PA)

Kharaj: flatwound bronze 0,92mm (N°20) tuned to G#1 (SA)

Laraj: bronze 0,56mm (N°24) tuned to G#2 (SA)

For more info about rudra veena you can visit www.rudravina.com and www.rudraveena.org